Hydrogen - it’s safe but scepticism remains

Efforts to develop hydrogen fuelled transport persist, despite difficulties and scepticism. But it appears that regardless of other challenges, safety should not be a barrier to adoption.

The search for hydrogen power

Hydrogen has the potential to lessen the world’s reliance on fossil fuels. But opinions are currently varied as to how hydrogen will play a role in achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. In particular, there is no consensus as to how it should be used in the transport sector. Techno agitator-cum-mystic Elon Musk has come out as a sceptic, even going on record to say that hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles are “mind-bogglingly stupid.” On the flip side, media petrol-head James May has reportedly said that his hydrogen powered Toyota Miraj is ‘the nicest car’ he has ever owned. All transport modes are grappling with how to use hydrogen and seeking to make it viable. So for transport safety professionals an obvious question to ask is: How safe is it?

How the magic happens…

Hydrogen fuel-cells (or ‘fool cells’ as Musk calls them) work by stripping the hydrogen molecules into protons and electrons in the presence of a catalyst to drive an electric circuit. So hydrogen fuel and atmospheric oxygen are turned into electricity, heat and water. This is all very elegant and provides opportunities to reduce carbon emissions. The water serves an additional purpose as it can be used to cool the stack of fuel cells that is needed for usable power levels. For land-based vehicles, regenerative braking tops up an on-board battery for complementary power and to cope with electricity demand peaks.

Lighter than air

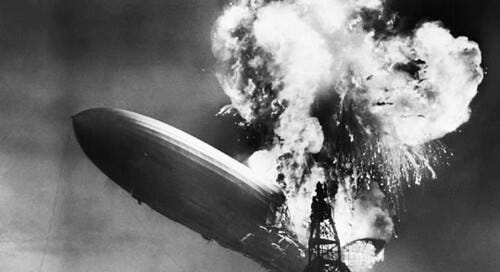

The German hydrogen-filled airship, the Hindenburg, dramatically exploded over New Jersey, USA in 1937: 84 years later, the image of that burning airship still lingers in the memory. However, the Hindenburg did not use fuel cells - it was simply a big hydrogen balloon. And much of the fire risk in that accident came from the airship’s diesel engines. Nevertheless, it serves as a reminder that, as a safety engineer, the first questions for any new technology are: what are the hazards of using it? And what needs to be done to make the resulting risk acceptable?

In the automotive sector, significant work has been underway for many years to understand and promote the safety of hydrogen. When hydrogen is present in the air in the right concentration and there is an ignition source, a large explosion is possible. Hydrogen is lighter than air and stored in high pressure tanks and therefore any rupture will tend to vent upwards in a narrow column, dissipating quickly in the open air. The key hazard is the build up of the gas, from a leak or tank breach, in an enclosed space. Not surprisingly, tests in the automotive sector also focus on the integrity of the tanks - even to the extent of showing that they are capable of withstanding armour piercing bullets.

Another safety concern - which also exists with battery powered vehicles - is the lack of combustion engine noise. We’re all used to listening out for the sounds of vehicle engines and even discerning speed and distance of a vehicle from what our ears tell us. In recognition of this US and EU laws coming into force now require artificial engine noise for such vehicles.

So those are the principal concerns. Is there anything that we aren’t thinking of? Regular readers will not be surprised to hear me flag the potential for software errors or remote cyber sabotage. Vehicles will inevitably be equipped with arrays of sensors and actuators including ones to to seal fuel lines in case of the detection of a hydrogen leak. Or course this makes the computers that read and activate such sensors safety critical.

Who is doing what?

Aviation is looking to hydrogen as a potential solution to its strategic environmental challenges - but for the foreseeable future it doesn’t seem it will be feasible for anything other than small planes and short haul flights. Shipping has moved its attention to ammonia rather than hydrogen because of its better energy density and ability to be stored at higher temperatures.

Rail seems to be the most opportune domain - in circumstances where the cost of electrification infrastructure is prohibitive, long travel distances are needed and there is readily available hydrogen for refuelling. The first hydrogen fuel-cell trains in Europe were recently launched by Alstom and Siemens is also investing in this technology.

Hydrogen car projects also continue to proliferate, despite Musk’s ridicule, with Prince Charles recently taking a drive in a hydrogen electric car in Wales and long term plans in place to use hydrogen powered trucks and buses in China. One attractive property for the automotive sector is convenience: where hydrogen is available, you fill the tank with gas, rather than waiting for a charge.

What’s next?

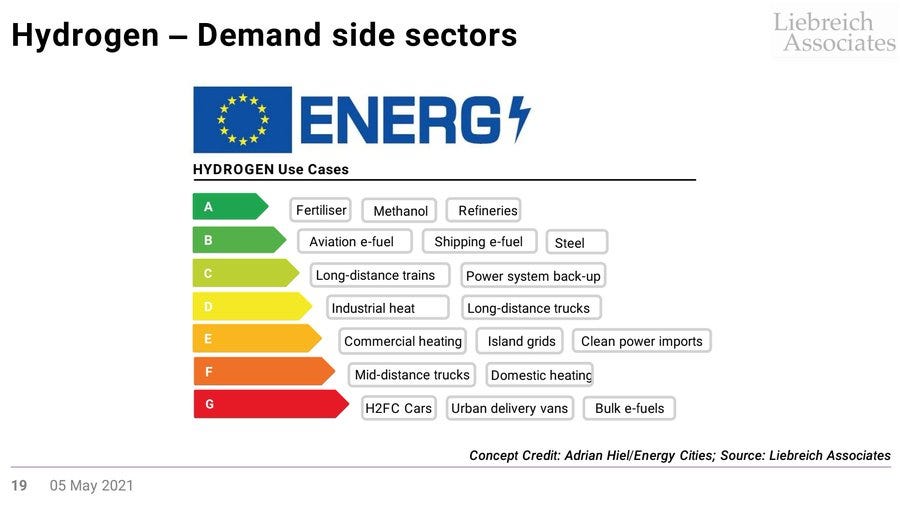

Some have argued that fossil fuel industries are funding the wrong projects from the basket of hydrogen applications to retard progress away from fossil fuels. A ‘hydrogen ladder’ is used to show where the priorities should be - industrial applications are considered to to be the most important, with trucks and cars much less of a priority.

It is certainly true that hydrogen vehicles will always consume two to four times more energy than their battery equivalents. This is simply due to the laws of physics. Hydrogen is also not yet produced in sufficient quantities to allow unconstrained progress on all fronts. Regardless of where this debate goes, it seems that hydrogen will retain some niche applications in transport: a point to note is that there do not appear to be any insurmountable safety issues associated with its use.

The next issue

I hope you enjoyed the this edition of Tech Safe Transport. In the next issue I’ll be taking you through yet another topic on the safety of modern transportation. Please subscribe now so you don’t miss it.

Thanks for reading

All views are my own and I reserve the right to change my opinion when the facts change. If you have any thoughts or comments please feel free to send me a message on Twitter. Many thanks to my editor Nicola Gray. The cover image is "Hindenburg Disaster" by e-strategyblog.com is licensed with CC BY 2.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/