The Ladbroke Grove Rail Accident: 22 years on

As the anniversary of the most pivotal event of the modern British railway era arrives once again, what are its lessons for the coming period of change?

An era-defining event

Even after 22 years, the Ladbroke Grove rail accident remains for me the defining event of the modern railway era in Britain. More so even than the rail privatisation that preceded it by five years, or the subsequent collapse of Railtrack.

Ladbroke Grove occurred barely three years into my now quarter century career on the railway and I witnessed first hand what a remorseless gut punch it was for so many who were affected or engaged through their personal connections or professional duties. When the accident happened on October 5th 1999, I had just moved from a job designing railway signal heads to a role in independent safety assessment of rail assets. I therefore felt very close to the issues of the day and this instilled in me an indelible sense of the permanent duty those of us working in the sector have to make sure that the lessons of the accident were learnt and never forgotten. Looking back, I can now see that I have spent my entire career ensuring that such an accident never happens again.

The accident

The immediate cause of the disaster was a train passing a red signal: signal SN109. The driver - Michael Hodder - who was one of the thirty-one people killed in the accident, had only been qualified for two weeks. The inquiry by Lord Cullen that followed, concluded that his training had been insufficient and bright sunlight had probably hindered his sighting of the signal, which was difficult to discern.

The resulting head-on collision was catastrophic and exacerbated by the fire that arose in its immediate aftermath. I won’t describe the consequences here, but those who are unfamiliar with the horror of that day should read some of the testimonies of the first hand witnesses who have bravely spoken about it, in particular Pam Warren - who has tirelessly shared her experiences as one of those who suffered life changing injuries as a result.

Learning from Ladbroke Grove

Lord Cullen’s inquiry rightly did not focus only on proximate causes. The accident was found to be the final release of pent up legacy issues, including many that had been festering since the major disruption of rail privatisation. Fundamental issues were raised addressing wide ranging topics from driver management, signalling technology, scheme design and rules, and regulation.

Part 2 of the inquiry focused on with the management of safety and the regulatory regime. It sought to stress the importance of leadership and safety culture in the sprawling and fragmented industry. The current organisational and regulatory structure of the railway and many of its independent assurance bodies and reporting roles - including the RSSB and RAIB - were set by that report and have evolved only incrementally to this day.

Industry improvement

The railway industry in Great Britain has come a long way since that dreadful accident. As passenger numbers continued to grow through the 2000s and with the renewed focus on safety culture and leadership, Britain’s railway safety performance has undoubtedly improved. In recent years it has regularly been the best in Europe. The ‘risk-based’ approach of the UK and the sharpened focus on accountability for safety following Ladbroke Grove, led to an unintended safety dividend for rail from privatisation. Contrasting, equivalent and complementary responsibilities created a natural tension between the train operators and Network Rail, and a culture of open safety reporting and safety focus emerged.

I found in my time as Safety Director of RSSB that this environment was envied by the safety leaders of neighbour countries even as some who were more used to a monolithic, standards based approach to safety, critiqued its excesses as the ‘English Disease’. Uncompromising safety assurance occasionally irked project managers too, when their failure to adequately consider safety risk at the right time occasionally led to project delays. But the improvements in safety performance, in a period of burgeoning passenger numbers, tell their own story.

Britain’s past safety record will not persist by default. Risks tend to evolve and find a way through our defences. There are adverse trends at the moment around passenger and public behaviour and a new lack of appreciation of the danger of the railway environment as people return from COVID lockdown.

A critical debate at the time of the Ladbroke Grove rail accident was about the cost and necessity of fitting of Automatic Train Protection (ATP). Now, finally, this is happening on the railway industry with ambitious plans in place for the fitment of ETCS across the network. ETCS is inherently safe but digitalisation shifts our risk and assurance needs more to areas like software assurance, data configuration and cyber security. A future challenge will be how the railway maintains its ‘Technical Sovereignty’ in the post Brexit world, and gains assurance of systems that it does not fully control.

Generational change

The publication of the Williams-Shapps plan for rail has initiated what is expected to be the next generational change for the railway. As we move into this period of transition, with the development of the Whole Industry Strategic Plan, it’s clearly time to dust off the Ladbroke Grove Inquiry Report. There are unwavering safety principles that need to be respected in any shifting of the tectonic plates of the industry. Some (but not all) of the points to consider are:

Fragmentation of the railway by privatisation didn’t of itself create the circumstances in which Ladbroke Grove occurred. Poor safety culture and leadership did. Similarly, removing those organisational interfaces won’t help keep the railway safe without those safety pre-requisites being maintained. Remember, the monolithic railways of Europe are currently less safe than the ‘fragmented’ UK railway of today.

The railway is under huge cost pressures and projects need to be delivered efficiently and on time. But we mustn’t let this pressure drive a new culture where safety activities are blamed for poor project delivery. Good safety is good business, particularly in the long term.

Robust safety evaluation - with strong independent challenge - is the proven way to ensure that projects are effectively and safely delivered in any sector. Strong checks and balances must be in place, and this needs serious focus as accountabilities are centralised, the government inevitably takes more control and railway technology becomes more global in nature.

Ladbroke Grove triggered a fundamental culture change in the industry. There is a duty to ensure that this culture pervades the generational change that is upon us. Ultimately, that is the only way to make the Great British Railway the success we all desperately want it to be.

The next issue

I hope you enjoyed the this edition of Tech Safe Transport. In the next issue I’ll be taking you through yet another topic on the safety of modern transportation. Please subscribe now so you don’t miss it.

Thanks for reading

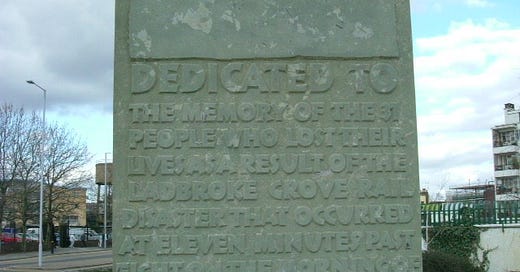

All views are my own and I reserve the right to change my opinion. If you have any thoughts or comments please feel free to send me a message. Many thanks to my editor Nicola Gray and to Phillip Perry for use of the picture, which is of the Ladbroke Grove rail crash memorial.